Unlike some of the other events in the US Coffee Championships held in April at the Specialty Coffee Expo in Seattle, the Brewers Cup and Barista Challenge are high theater, mini-plays performed for your mind and heart as much as your eyes, nose, and taste buds. If you’ve ever attended coffee tastings where a host tells the story of a coffee’s origin, provides tasting notes, and serves the coffee, these events mimic that experience. In competition, the storytelling is more refined, polished, and timed. The baristas and brewers even choose a soundtrack to play underneath, adding music to capture a particular mood or theme.

Storytelling about coffee, with coffee. What could be better?

(Read Part 1 here for an introduction to coffee competitions and an inside look at the Specialty Coffee Expo’s latte art battle.)

I watched Rebecca Woodard in the open service portion of the Brewers Cup [tasting notes: pleasant aura of self-confidence, exotic taste-note-forward tasting notes, complex commitment to marginalized communities]. She would eventually win with her exquisite knack for storytelling, an inventive brewing method, and, I would assume, great coffee, if it tasted and smelled even a fraction of how she described.

Woodard (@beccacantread on Instagram) is the wholesale account manager and head trainer for George Howell Coffee in Acton, MA. George Howell was an early influencer and contributor to the notion of specialty coffee in the United States dating back to the 1970s. Starbucks acquired Howell’s first business, The Coffee Connection, in 1994 when it had 24 stores. Howell remains a revered name in specialty coffee, co-founding Cup Of Excellence in 1999 and opening George Howell Coffee in 2004. One of his innovations was to freeze raw coffee so that its quality did not degrade, given that coffee is typically only harvested once a year. In doing this, he can also help producers compare crops year over year.

George Howell’s leadership team is mostly female, according to Woodard, and staff details on the company’s official website back this up. This is still a rarity that many people in the industry, like Woodard, are trying to change.

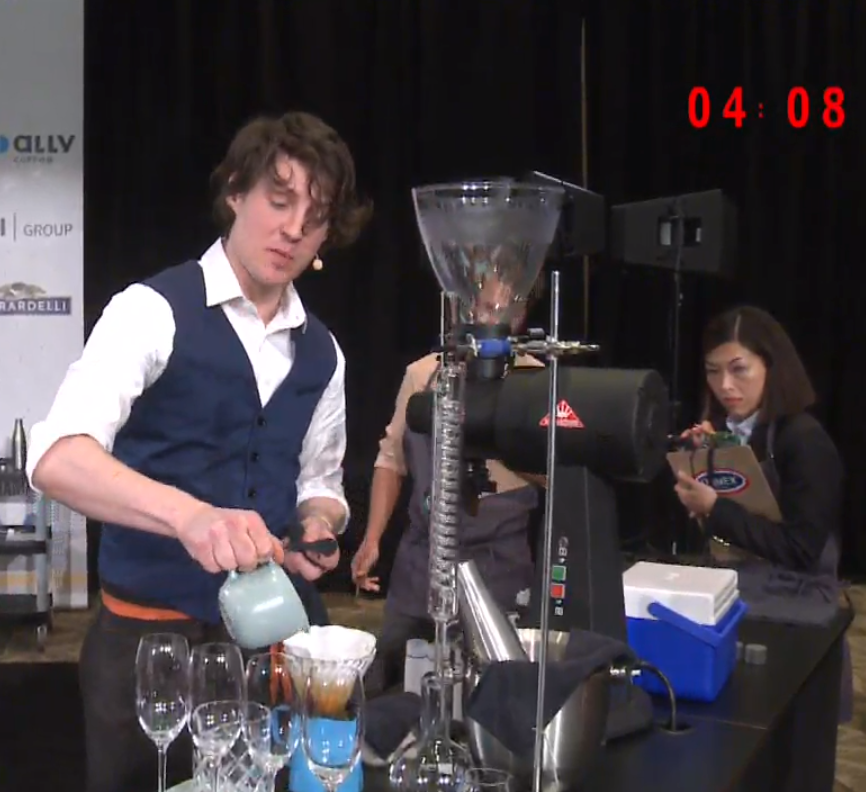

(Photo captured from competition livestream.)

Woodard brewed using an inventive, home-grown contraption feeding a Walküre Bayreuth brewer, a century-old German device that I suspect isn’t found with great frequency during competition.

(Apropos of nothing, Walküre is pronounced just as you would say Valkyrie, which is a female spirit-helper of the god Odin in Norse mythology. A Valkyrie chooses who dies in battle. Coincidence?)

The contraption includes what looks like a miniature ballet bar (seen in the foreground of the photo above), upon which three brew kettles rest from their handles, all sitting inside a custom-made wooden trivet. Woodard was able to pour three cups simultaneously, with precision and consistency (you can see the final result in the photo below). Some barista-focused company must surely now be working on making something like this.

The Walküre is a multi-tiered ceramic brewer. The top chamber contains six small holes in the bottom that spread hot water evenly over the grounds resting in the bottom chamber on a cross-hatched grid filter built into the pot. The top chamber is closed so that the Walküre retains the water’s heat, which ensures maximum flavor extraction. The Walküre process creates a suspended brew bed that separates the fine grind particles and allows the coffee oils to pass through the filter more freely–a paper filter would normally catch some of those oils and the fine particles. And yet the coffee grinds also act a bit like their own filter. Proponents claim that it results in a “cleaner” cup.

(Photo captured from competition livestream.)

Woodard said she chose the method to highlight the liquor-like body of the coffee she used and because the cups retained the aromas best. She noted that there would be some sediment in the cup, and she encouraged the judges to stir it in before drinking because doing so would heighten the coffee’s sweetness. She also instructed the judges to sip using a cupping spoon, rather than drinking out of the cup. No detail is too small to exploit.

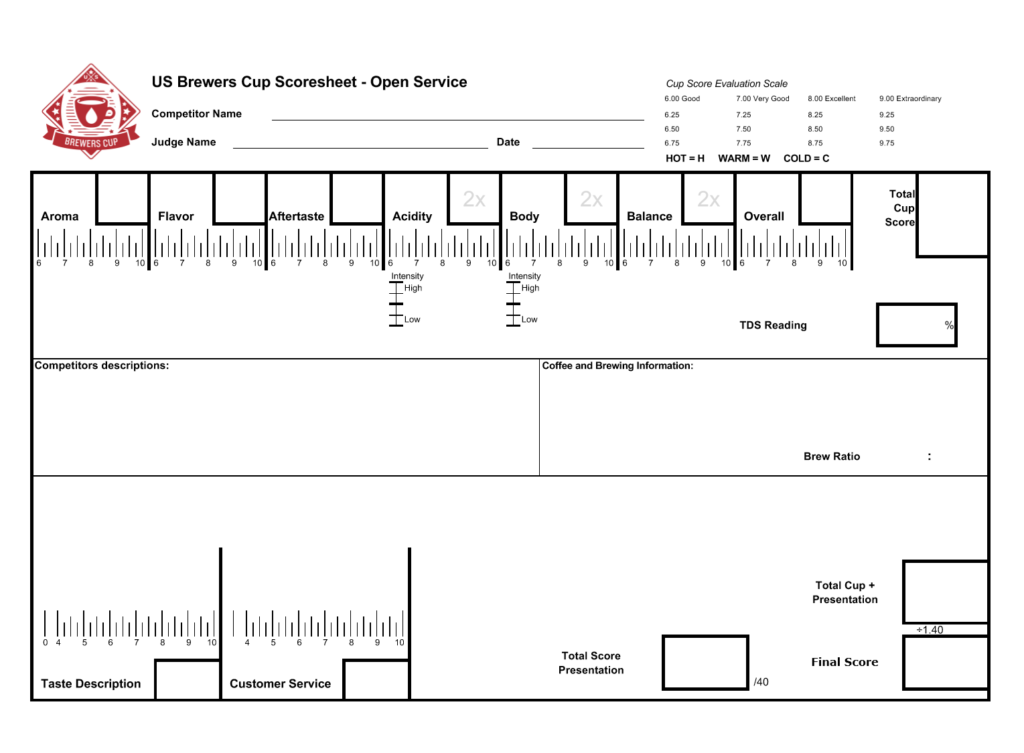

Competitors provide “recipe” details that include coffee-to-water ratios, bloom time (an initial process of wetting the coffee grinds to allow the natural gases to escape before brewing), total draw-down time (the amount of time it takes for the water to leave the grinds and complete the brewing), as well as any other pulse pour measurements and timing during brewing, and TDS (total dissolved solids) targets–expert brewers shoot for TDS targets in order to hit ideal extraction percentages. Many professionals and enthusiasts use a special refractometer to take these readings when dialing in a brewing method.

In other words, yes, there is math, there is chemistry, there is physics. Coffee even has its own lexicon–bloom, draw-down, extraction, TDS, first crack, slurry.

Beyond the science, there is also an art to brewing the perfect cup, which is fitting, because there is also artistry behind the story of a coffee’s journey from plant to cup. Practically every competitor regaled the judges and the audience with origin stories. In Woodard’s case, the coffee was a special Geisha varietal from Panama, sourced by Joseph Brodsky, CEO of Ninety Plus Coffee, and the company’s Geisha Estates GM Jose Alfredo. Brodsky and Alfredo helped revitalize an old coffee farm in the rainforest that had been turned into a cattle farm, Woodard said. A gorgeous documentary on the Ninety Plus website backs that up.

The Geisha was grown in Nanolot 236, a small group of farm lots created for experimentation purposes. The coffee is grown 1600m above sea level in the shadows of a volcano and benefitting from the crosswinds of the Pacific and Caribbean oceans. Ninety Plus uses a secret fermentation process—Brodsky would only say in an email: “We can tell you that it depends on cold processing temperatures and controlled application of local microorganisms. The coffee is dried in fruit.” The topic of coffee fermentation using specialized yeasts is a newer area of research and experimentation, but it would seem that Brodsky’s organization is already employing some techniques, apparently with a premium outcome—intense acidity and big fragrance, according to Woodard.

Woodard described floral fragrances, including jasmine, lilac, and freesia, but also orange oil and strawberry. She described the flavors of the coffee when it was at its hottest (pineapple and a more fruity single origin dark chocolate bar–did I mention the attention to detail?), when it was warm (jackfruit, orange peel, nectarine, and soursop), as it cooled (a deepening of the orange peel creating a taste more like orange liquor). Woodard also described an intense passion fruit curd, bergamot-like floral notes, and amaretto, and an aftertaste of summer fruits and white sangria.

For my virgin competition ears, these less like tasting notes and more like a tasting treatise. With my inside voice, I wondered if perhaps it would have been easier to tell the judges which flavors they wouldn’t taste.

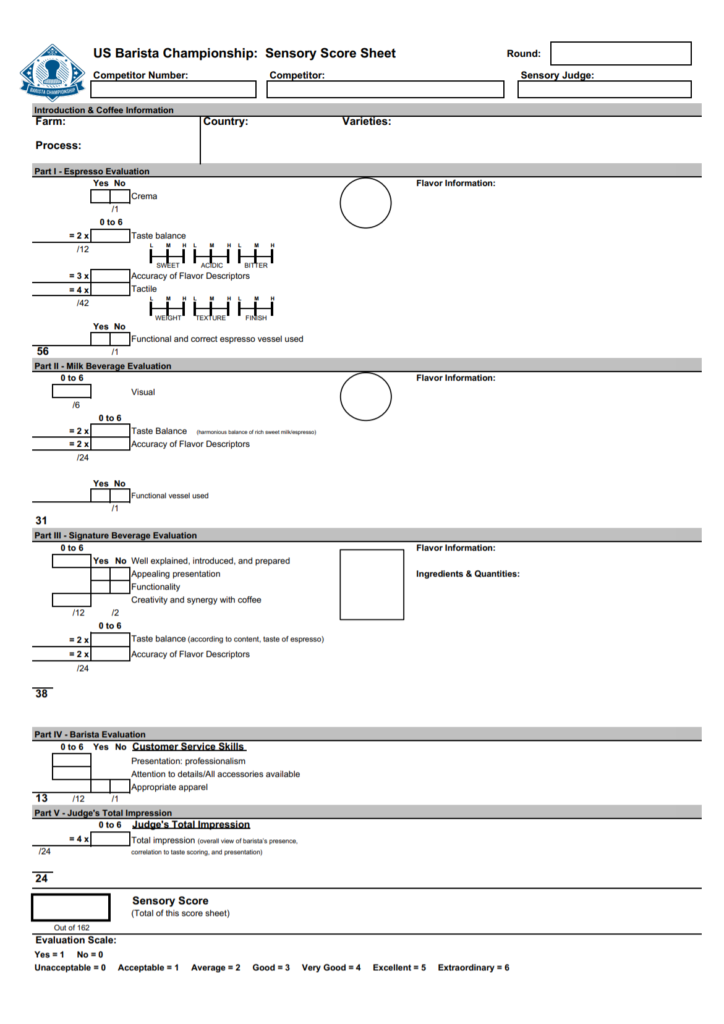

I’m detailing some of this here because as specific as those notes are, the judging experience has to closely match what Woodard says (see scoresheet above—we’re not playing around here). I’m sure the judges have deep sensory training, and because Woodard won, I’m hopeful they’ve also tried passion fruit curd (think creamy, silky passion fruit), bergamot, soursop, and jackfruit. Woodard told me via email that the judges said some of tasting notes were a bit obscure, but it clearly didn’t heavily impact her scores. She added that the coffee she brewed was unique and that “the most novice taster would have been able to taste all the things I said.”

Which leaves me only wishing I had.

Baristas Make Coffee Equivalent of Food Porn

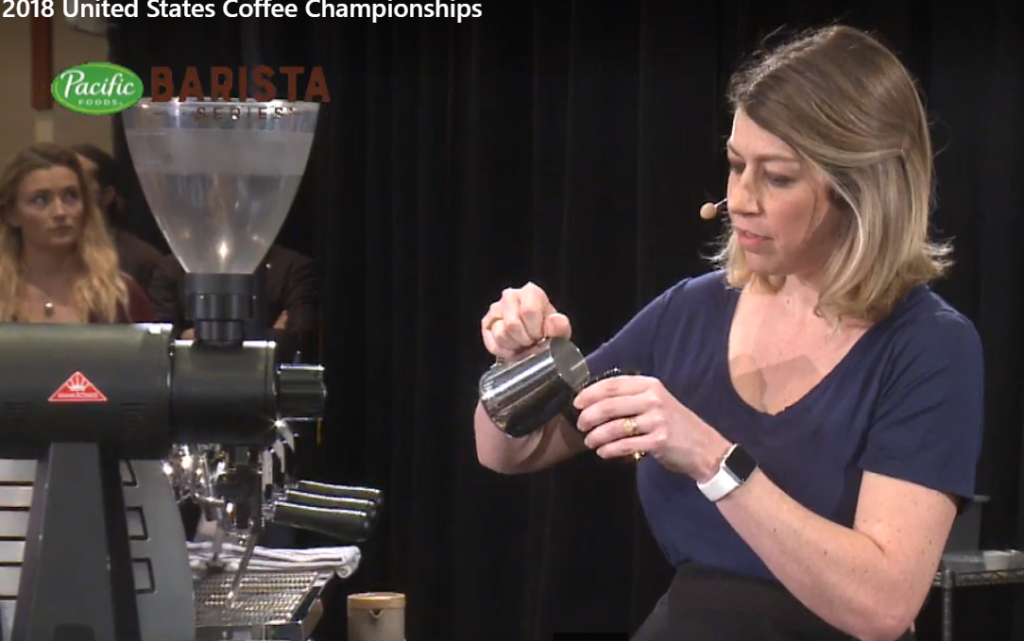

The Barista Series competition is based on a 15-minute performance (longer than the Brewers Cup, which is timed but doesn’t necessarily have a time limit) where the contestant must create an espresso, a milk-based drink, and one specialty drink.

The event is judged on taste and innovation as well as performance. One judge told me: “We’re looking for the best coffee ambassadors.” The judge said that for taste, not only should the cup experience match what the competitors say, but complex flavors were paramount.

(Photo captured from competition livestream.)

I watched a handful of contestants, but a couple stood out. First, Andrea Allen, the owner of Onyx Coffee Lab in Springdale, AK [tasting notes: did someone say applewood smoke? #watermatters, you had me at blowtorch, disappointing lack of Arkansas twang] who used a natural-processed Geisha varietal from the Nariño region of Columbia. Geisha coffees, which are rare and expensive, have huge flavors, making them a favorite among some of the competitors.

Allen’s presentation stood out for its thematic storytelling. While telling the judges and audience about the coffee’s origin, she wondered aloud about the future of that coffee farm and more broadly about whether the coffee industry could successfully entice future generations of coffee producers, especially given the economic challenges that farmers face. Onyx is big enough to employ 78 people in its various shops, and Allen said that she couldn’t wait to see many of these employees leave to start their own businesses, hoping that this could be part of her own legacy—a laudable and bold statement.

(Photo captured from competition livestream.)

Allen used different water for each preparation—a mineral water for her espresso to soften the acidity, distilled water in her cappuccino to enhance its body, and filtered water from a pond in front of her house for her signature drink to capture its watercress flavors. Most experts, when discussing brewing methods, emphasize the importance of water quality, given that it makes up more than 98 percent of a cup of coffee. You can even purchase mineral enhancements for brewing water, presumably so that no tasting note is left unturned.

(Photo captured from competition livestream.)

Allen said she wanted to recreate the region of her coffee’s origin, with its sugar cane (and the aroma of burning it that lingers in the air in Nariño) and citrus, in her signature drink. “Instead of finding ingredients to fit this coffee,” she said, “I manipulated the coffee to fit the ingredients.” To her espresso, she added pressed sugar cane nectar, a watercress water infusion to mimic her pond at home, a charred tonic bittermilk syrup, citric acid, and a finish of applewood smoke. All of this was housed inside a wooden bowl (pictured above) to contain the smoke. She provided a whiskey ice rock to cool the liquid to 100 degrees where, she said, it would taste its best (I did mention the attention to detail, right?).

(Photo captured from competition livestream.)

Allen did not win the Barista Series. She finished fifth. Only the judges tasted her drinks, but her presentation won me over.

(Photo captured from competition livestream.)

The Barista champion was Cole McBride, an independent (meaning, he wasn’t linked to a coffee shop or any other entity). [Tasting notes: undertone of mad scientist, the anxious energy of Edward Scissorhands, heavy flavors of drinking instructions, a will to win finish.] Unlike some of the other competitors, he didn’t have an overarching, inspiring message or theme. This was about the coffee.

McBride had been on this stage a time or two. He was dialed in, and his attention to detail and drink invention left the impression of having watched some sort of coffee surgeon. His goal was to make memorable drinks, and he clearly did.

On the coffee, McBride teamed up with Velton Ross’ Velton Coffee, a roasting company in Everett, WA. They selected an Ecuadorian Typica varietal from Juan Peña, a coffee McBride said had a medium, silky body, tropical aromas, tastes of soft pineapple, a fruit zest acidity, and a sweetness like that of demerara sugar—it seems tasting precision knows no bounds. (I say that with the utmost jealousy.)

McBride spun his showcase differently than other contestants I saw. First, he spent about half of his time just doing prep work and talking through his coffee, his hands seemingly with a mind of their own. He slammed out all of his drinks one after the other in the second half of the service.

(Photos captured from competition livestream.)

He also served his signature drink first, another divergence from other competitors. It was an espresso champagne. He “drew” the espresso extra long (slow) to enhance its floral qualities, used a condenser (pictured above—second and third photos in the gallery) to bring the drink’s temperature down (and filter the coffee a bit), a carbon filter (also pictured above) to get rid of any sediment and the espresso’s crema (that milky layer on top) so that the bubbles created by the CO2 would be even tighter and more sparkly. The crema, he said, doesn’t mix well with the CO2. He applied two separate CO2 charges before serving the drink.

(Photo captured from competition livestream.)

This entire process, including the application of citric acid and a simple syrup that used yuzu zest (infused for 24 hours) made the drink more citrus like, with some honeysuckle flavors, McBride said. He even instructed the judges to swirl the drink four times (emphasis mine) before taking in the aroma.

McBride’s precision was also evident in his espresso course, where he used frozen cups. The idea was to bring the temperature of the espresso down to 110 degrees where, he said, the flavor is optimal.

Sentiments and Sediment

These presentations are the idealistic representations of a true coffee experience. Too often your favorite specialty coffee shop has a long line, or the baristas are busy, or, worse, lack the knowledge or curiosity to share even a small piece of what these presentations offered. I have only occasionally experienced something like it, and it’s always at my own prompting, and typically at only the best coffee shops. A George Howell representative said in an email that “there’s definitely a marriage of the art and the pragmatic in the real-world cafe . . . . wanting to give the customer as much info as we can impart without going overboard.”

It’s a fair point. If you spent five or 10 minutes listening to all of the details, Rebecca Woodard or Cole McBride or Andrea Allen-style, of the $5 cup of specialty coffee you were pondering, your response might be “take my money.” Others might roll their eyes at “soft pineapple,” impatiently waiting for the finished cup. The George Howell representative added that “the competitions are tailored to showcase the best, in an atmosphere that’s designed to call attention to and celebrate the unique.”

For her part, Woodard told me that the world of competitions is shifting, hueing toward making these special coffees more accessible to consumers. “Part of the reason I wanted to pour three kettles at the same time,” she said, “was to maximize efficiency like we all try to do in our cafes.” That efficiency, by extension, might give the barista more leeway to tell at least part of the coffee’s journey. “During a slow time, you should be able to chat with the barista about the coffee they’re serving,” Woodard said.

Woodard told me that she hasn’t yet decided whether she’ll go to the World Championships later this year. The Brewers Cup is being held in Dubai, part of the United Arab Emirates, whose human rights practices have been condemned by organizations like Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, and well chronicled in the media. Woodard said that she is a queer woman, which is unlawful in Dubai, making the trip dangerous. The decision by the Specialty Coffee Association (SCA) and its competition body was widely derided, including in a strong rebuke from Sprudge, a well-read publication in coffee circles. The publication reported that Blue Bottle, perhaps the biggest specialty coffee retailer in the U.S., resigned from the SCA. In response to the coffee community’s outcry, the SCA created a deferred candidacy program, allowing winners from 2018 to defer until 2019. It did little to deflate the situation.

Woodard said, via email, that she is participating in these types of competitions to “speak up, empower, and try to make real changes happen in our community.”

She’s a winner, no matter how you brew it.

[Headlines rejected for this article: I Don’t Know Jack, But I Know My JackFruit; Is That A Coffee Condenser In Your Pocket, Or Are You Just Happy To See Me?; Norse God Odin Working On Secret Fermentation, But Probably Involves Mead Yeast.]