Danny’s eulogy. July 22, 2022.

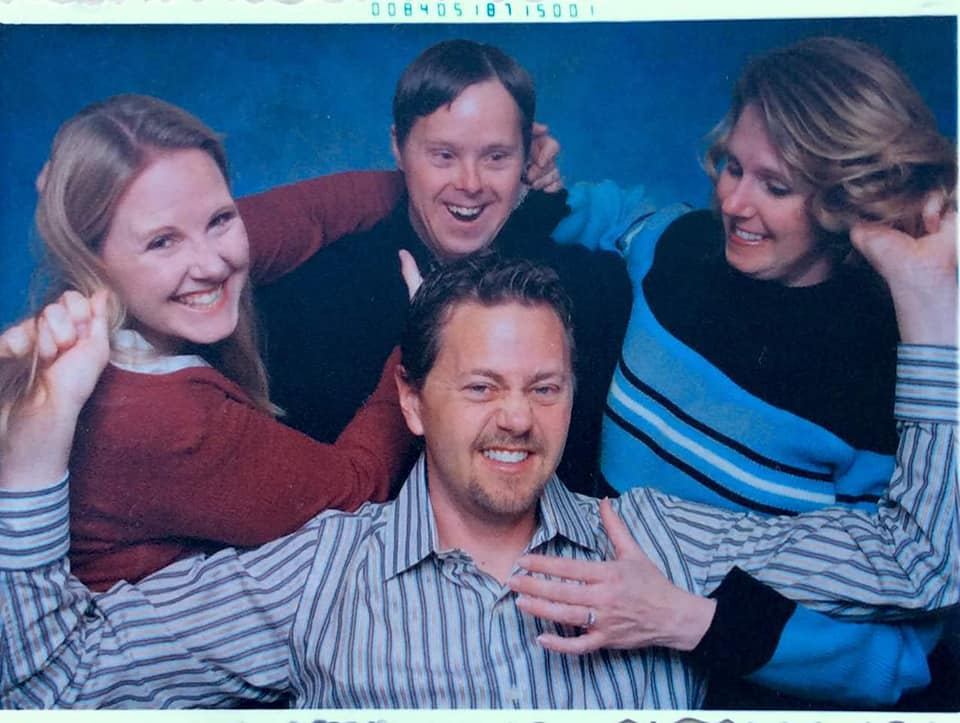

I’m often asked what it was like growing up with Danny. I could never quite figure out how to answer that. Growing up with Danny is all I knew. You may as well have asked me what it was like to grow up with my sisters—no picnic, by the way.

But OK, let’s talk about it.

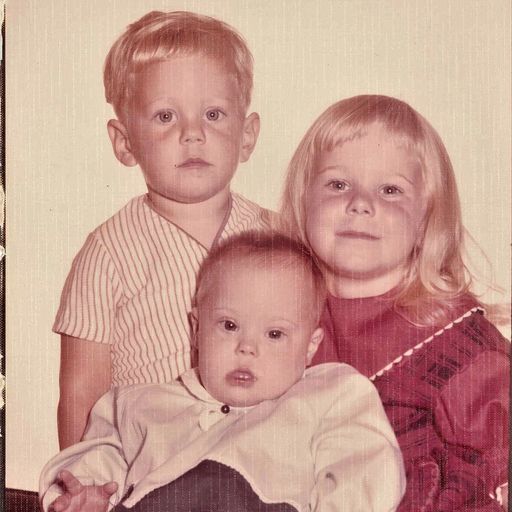

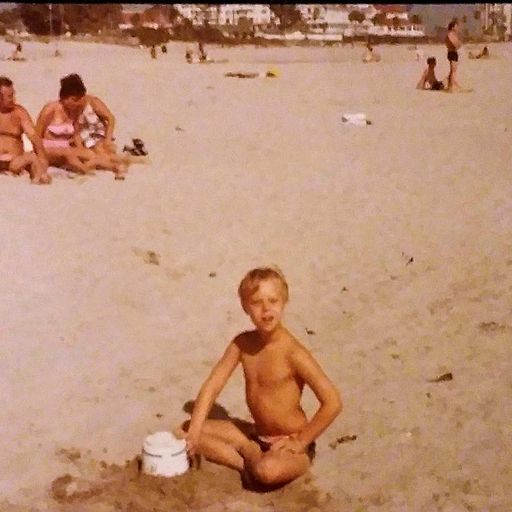

It was magical. I wish you could have been there. It was an absolute celebration of living. Every day, Danny exposed his innocence, his raw emotions, his capacity to love. Danny was born with a heart murmur, but for the rest of his life, he was our family’s roaring heartbeat.

To outsiders, he may have seemed slowed by physical and mental handicaps, but I was always jealous of the absolute freedom he had to be, unapologetically, himself.

And yet, all he wanted was to be like Linda, Misty and me. He wanted an allowance, to go to school, to have a girlfriend, to play a sport. At dinner, we all teased each other, and we gave it to Danny in equal proportions. And he gave it right back.

We learned early on that whatever pace we set, he would try to match it. Growing up with Danny meant learning that limitations were elastic. Down Syndrome? For Danny, they should have called it Up Syndrome.

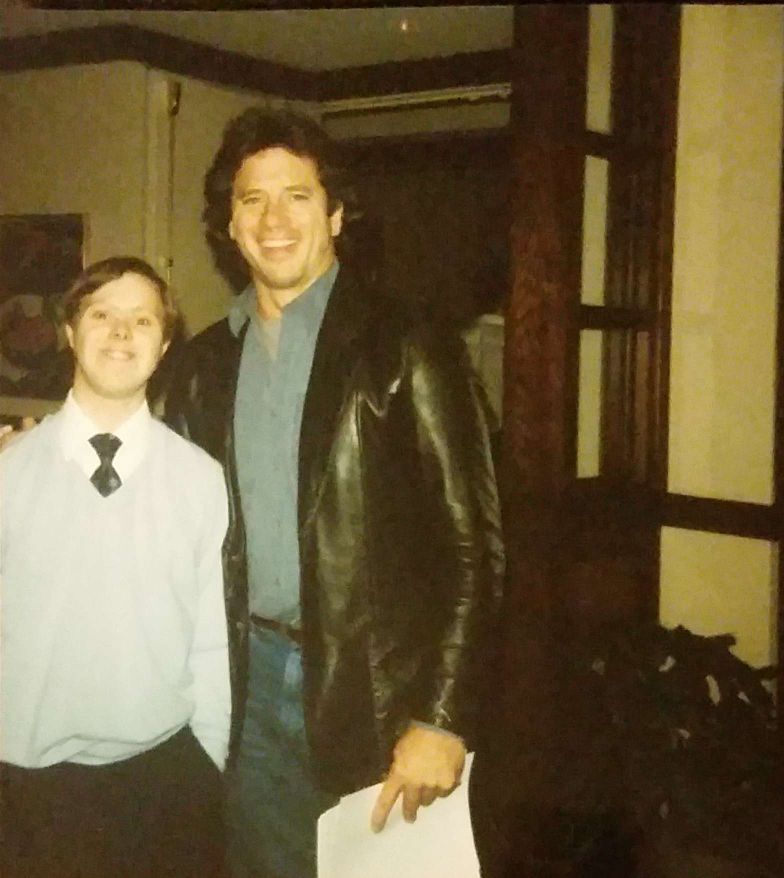

Danny made every day entertaining. He loved The Dukes of Hazzard. He once rolled down the car window when I was angry with him and called for Bo & Luke to come help.

There was the time Danny was receiving an award at a Special Olympics banquet. When Danny went up to accept his award, he stopped, held up the award and declared: “this one’s for OJ!”

And Danny loved to sing. We’d go for a drive, and he would sing loudly and so far off key, I think he was inventing new notes; and he would always be 3 words behind the song. We didn’t care.

Back in the late 1970s, the Bee Gees had a popular song called “More Than a Woman.” <Sing the chorus> But what Danny thought they were singing – and sang himself – was <Bald-headed woman . . . > We couldn’t wait for that song to come on the radio.

Around this time every year—yes, Summer—Danny would give us his Christmas list. Usually, he wanted a shirt and a mug from some university. The best part is what came at the end, which is where he would butter us up, telling us how beautiful we were, how smart, that we were the best brother or sister. We would each compare them, arguing about who’d gotten the most compliments.

But it wasn’t always easy. The world can sometimes be unkind. Wherever we went, people would stop to stare, make a comment, or sometimes move out of the way. It’s where I first witnessed the human capacity for intolerance.

We learned early on that we all had an obligation to make life for Danny as normal as possible. There was no wiggle room there. Our needs were important, but Danny’s were paramount.

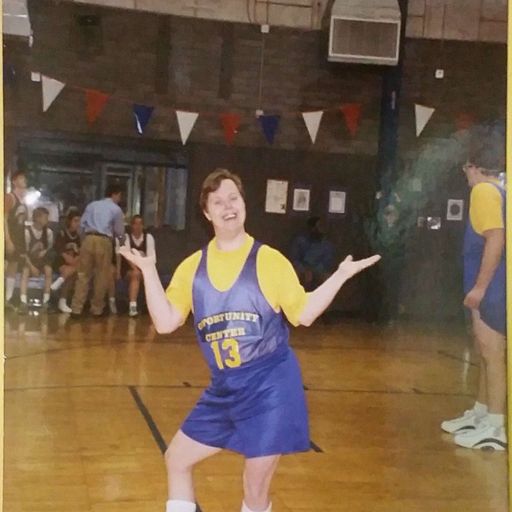

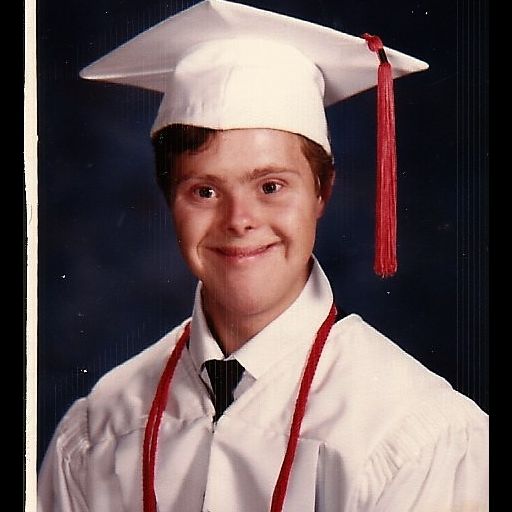

I doubt there’s anyone here who doesn’t know what Danny was able to accomplish athletically. He was an Olympic athlete . . . in everything.

But probably not many of you know how his Olympic journey began. His first sport was track- and-field. And he was fast. In his first 100-yard dash at the Special Olympics, he was winning so handily that he began to look around for the other runners, and as he did, he slowed down and someone overtook him and won. From then on, every night the family would gather on our sidewalk and run the 100-yard dash—running slightly behind Danny without overtaking him. The idea was to train him not to look back. And it worked. He never looked back – literally and figuratively.

That’s just what we did. Our family created a mystical, alternative universe. We bent and tilted and shaped the world so that Danny would never see himself as different, so that he felt an equal player in it. He would be able to read, to do math, to make his own lunch, perform chores, be a church usher, work at a grocery store.

Danny attended Huntsville High School. One Spring, my sister, Linda, asked Danny if he had a prom date yet. He didn’t, so she convinced him to call the girls in his class–he of course had their numbers. But by then, all of them had dates, and Danny was inconsolable. So Linda took the world and tilted it: she told him she would go with him to the high school prom. Danny was thrilled, and he showed off his big sister at the dance. This is what we did.

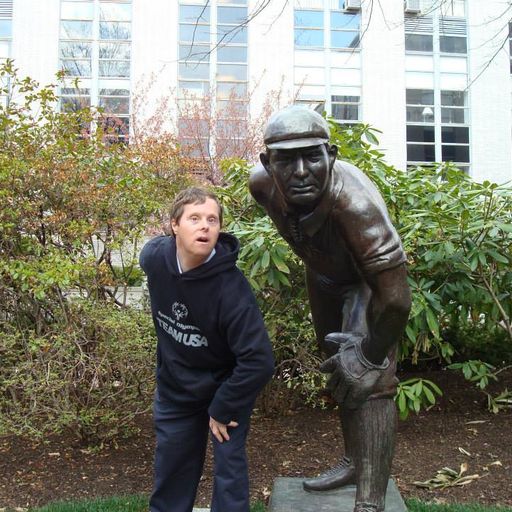

High School eventually was done with Danny, but he wasn’t really done with it. He continued to buy the year books, go to games, and over time he started to pine to go to college. For years, he talked about it—I have letters from him where he was narrowing down his decision. It was heartbreaking. A year or so ago, my mom got the bright idea to start Danny Nelson University – a made-up school where she would work with him to sharpen his mind as he embarked down the road of dementia, but also to give him an idea that he was going to college. To bend the world again. Because this is what we did.

As we created this world for Danny, moving the obstacles out of Danny’s path and softening the heartaches, a remarkable thing began to happen. You joined us in the bending and the tilting. You became our co-conspirators. You talked to Danny about football, took him to games; you teased him, you put him to work, you became his coach. You accepted him. Your kids became his friends and his protectors.

Back when we used to run that 100-yard dash with Danny in the neighborhood, it wasn’t long before the neighborhood kids would join, and there would be a dozen or more people lining up each night to run with Danny. Because that’s what you did.

You too put Danny at the center, you indulged his idiosyncrasies, tolerated his flip-flops from Alabama to Auburn to LSU back to Alabama. You brought him joy.

And yet, I suspect that your motivation wasn’t in helping us create our alternate universe. It’s because your lives, too, were enriched.

Anyway, there’d always come an end—to the fun, to the day, to the silliness. To the stadiums, the accolades, the applause, the newspaper and magazine articles . . . and when these days were over, we just had Danny. And really, that was enough.

Imagine what it would be like to wake up every day and see yourself as bigger than life in someone else’s eyes. Imagine knowing that no matter how badly you screwed up, you had a confessor whose penance was simply a hug. And just when you told yourself he probably didn’t quite understand, he’d say something that told you he did. Because that’s what he did.

And that’s what it was like growing up with Danny. It’s been an amazing life.

A better question now would be what will it be like without him. This is all we’ve ever known. Linda, Misty and I, we’ve all gone on with our lives, formed careers, raised families. But there’s really only ever been the Nelsons with Danny. He was our center. Our roaring heartbeat.

I know that for the rest of my life I’ll hear his voice, singing along, a few words behind and extremely off key, like the world was made just for him.