You’re allowed to simply enjoy the taste of good coffee. If you can pluck out familiar aromas and flavors, all the better. If you deem that $4 well spent, growers and roasters and brewers have done their jobs. Everyone is satisfied.

Appreciation is something beyond, a natural consequence of curiosity, gained from reading labels, asking questions, devouring books, or even visiting coffee farms. But if you want to see where the edges and boundaries are being pushed, go watch coffee competitions.

Yes, coffee competitions. Contestants even compete on the basis of how well they can taste coffee.

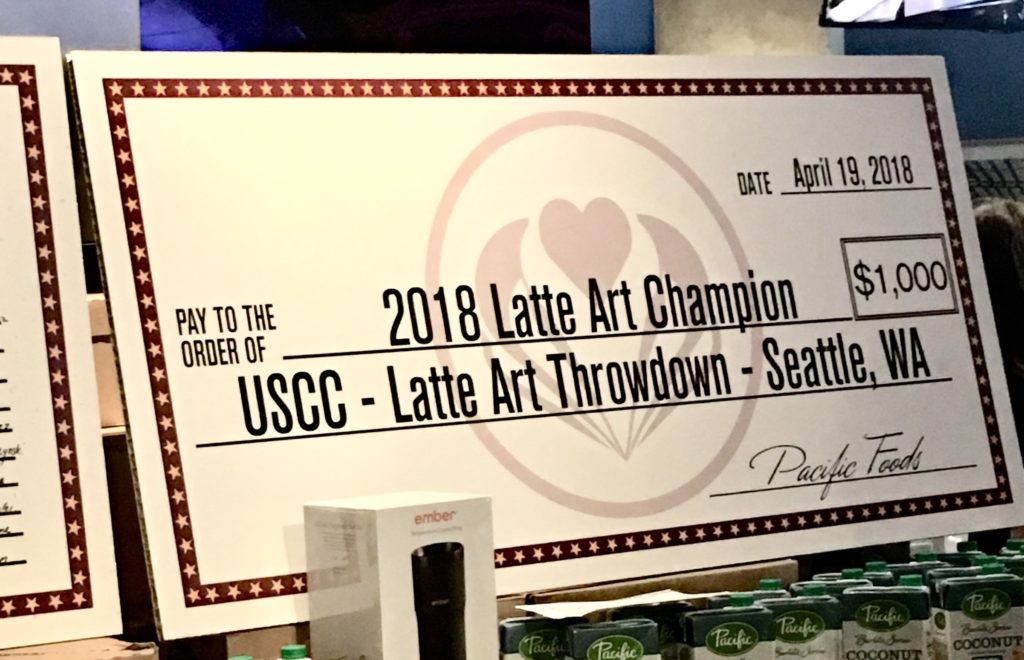

During the Specialty Coffee Expo’s kick-off party at Seattle’s Museum of Pop Culture in mid-April, dozens of attendees watched a latte art battle, with full-on bracketology, an emcee, sponsors, and prizes. The only thing missing was Las Vegas oddsmakers.

During the three-day Expo, the Specialty Coffee Association (SCA) also hosted a Brewers Cup, a Barista Series, and a Cup Tasters Championship, among others. Somewhere in the expo hall labyrinth was the Roaster Championship. All of this was part of the 2018 US Coffee Championships, fed by regional contests in Reno, NV and New Orleans, LA.

I saw a decorated latte art finalist argue relentlessly with a judge after losing. I saw inventive coffee contraptions. I heard flavor descriptions with such precise detail, I wondered if the judges were being served coffee or a fruit basket. I heard an obsession with detail that, outside of the competition room, may have led me to wonder what meds the competitors had been prescribed.

What stuck with me were the stories I heard, the inspirations behind the obsessions, the years of practice and experience, the communities connected by coffee, the struggles of the farmers who competed not on a stage but with the resources the earth doles out abundantly or scarcely or even furtively.

I wondered if the farmers whose names were uttered with hushed reverence in the competition hall would even be able to afford that final cup in a coffee shop in America.

[Tasting notes: An abundance of white males, with notes of man buns, extravagant mustaches, and ironic beards. A smooth finish of powerful women using the platform to spread change. A preponderance of Geisha, but probably not the kind you’re thinking. A refreshing aftertaste of “not made in America.”]

Latte Art: Of Milk, Tulips, and Pitchers

I’m easily mesmerized by the guilty pleasure of latte art. This is where the glitz meets the grind. It’s the barista equivalent of a chef meticulously plating a meal. The “And One” of a milk-based drink.

I watched the latte art competition standing next to Joseph Gonzalez, president, and COO of Espresso State of Mind in New York. He happened to be a competitor, but he’d already been knocked out by the time I arrived. He was unlucky enough to get an early draw against Lance Hedrick, a renown latte art competitor who ended up in the championship later that night. Gonzalez’ bad luck was my good fortune since he now had time to let me quiz him endlessly about how the competition worked.

Pacific sponsored the event, and the latte art had to be created using one of its alternative milk products (Oat, Coconut, Almond, or Rice). One key to making latte art involves building layers of texture with milk during the frothing, so you can imagine that figuring out which milk to use is key.

This contest was “free pour,” where contestants are required to simply pour freehand out of a pitcher. Other competitions allow etching, or the ability to draw inside of the latte using various tools, and the end results are more intricate. The free pour is more common, not just in competition but also at your local specialty coffee shop.

You’ll typically see hearts, Rosetta rosetta, and swans, Gonzalez said, and occasionally a phoenix. I saw a preponderance of tulip art at this competition, with all sorts of variations. Gonzalez said that this is because the tulip requires a go/stop/go action. Continuous pours are difficult using alternative milk. There’s also an inverted pour, which involves the barista starting the design one way, stopping, and then pouring in the opposite way to finish or enhance the design.

Contestants are judged on three main criteria. Clarity or contrast refers to how sharp the edges are and how much contrast there is between the milk and coffee, according to Michael DeJesus, one of the judges for the competition. A winning cup’s design must also have great symmetry. Finally, judges assess the difficulty of creating a design, something that’s much harder to judge when different types of designs–say a multi-stage tulip vs. a swan–go head to head, DeJesus told me.

(Above: Lance Hedrick competing at left; Derek Wessels making and delivering winning pour; finalist latte art; champion latte art.)

Derek Wessels, owner of Beagle Coffee Co in Fort Collins, CO, was the big winner. Although he has competed in many local competitions, this was only his eighth on a bigger stage, he said. He mostly practices by serving his customers, but he’ll practice after hours perhaps once a week. Wessels won with a 4-3 design, which is a multi-tiered (4 and then 3) tulip. He created a different design for each stage of the contest. In the end, he beat out Lance Hedrick, of Onyx Coffee Lab in Arkansas. Onyx put forth a few competitors in the various competitions, including the shop’s co-owner Andrea Allen (in the Barista Series).

In any specialty service, there are specialty tools. In latte art, the milk pitcher matters. Luckily, they’re affordable. Most everything else is not.

The picture (above) probably illustrate best why this tool matters. First, the spouts are different. Some are pointy, some are rounded. Some start deeper toward the bottom of the pitcher. Some start higher. Each of these impact the pour, from how quickly the milk starts its flow, to the speed of the pour, to the precision each spout type delivers, all of which instructs the design. In this way, Gonzales said, it’s like a chef’s knife: “you wouldn’t filet a fish with a butcher’s knife.” (Depends on the fish.)

Baristas must also factor in ergonomics–overall weight and weight distribution–and a pitcher’s thermal attributes. “If it’s coated on the inside,” Gonzales said, “you tend to have to aerate it [milk] more because it takes you a little longer to get what you are looking for.” On the other hand, pitchers that aren’t coated get hotter much quicker, so you may not have as much time to build the texture.

Wessler, the competition’s winner, uses a Rattleware pitcher. He said it’s really just what he’s used to. In particular, he said he likes how milk flows out. Its tip is not super pointy or flat. “Milk flows out without diving under the top of the espresso,” he said. “It’ll rest on top and give you really good contrast.”

I’ll go with the Rattleware too, then. Winners get the final word.

[Alternative headlines rejected for this piece: Better Latte Than Never; Better Never Than Oat Milk; Latte Artist Brawl Breaks Out Over Whose Tulip Is Best; Pitcher Perfect.]

Part 2 will cover the Brewers Cup and Barista Series.