(Tasting Notes: A Belgian influence, but the forager, not the waffle . . . nor the chocolate, although it was mentioned as a dream conduit for black sage. A warm trickle of potty humor with notes of sexual innuendo and allusion to dark arts. )

(Disclaimer: No animals were harmed in the making of this, except for the ants—not pictured due to . . . digestion.)

The biggest problem with traversing private land in the Angeles forest just outside of LA with Pascal Baudar, searching for wild plants and then concocting sauces or sodas or beers with them right in their natural habitat, is that now I can’t stop myself from hunting my backyard for more ingredients.

And it’s not just my backyard, it’s my neighbors’ backyards, it’s the freeway off-ramps, it’s empty lots behind buildings I spot while sitting at a stoplight. I’ve even had a dream where I’m running through an enormous field of oxalis.

Is that dandelion? Or are those sow thistle? Look at all of that mallow fighting for space in my neighbor’s urban farm. I hope that’s chervil and not poison Hemlock. If only Pascal were here . . . .

Sometimes with Pascal Baudar’s workshops, three hours turn into four, and still, you don’t want to leave. He’s knowledgeable yet humble, he has a ridiculous French accent (Belgian, but who says ridiculous Belgian accent?), and he’s endlessly funny, peppering his workshops and foraging walks with patentable quips. Like when he calls his hot sauce a “self-abuse sauce,” because no matter how much pain it delivers, a little while later you come back to it for more.

Foraging For Food

Baudar conducts workshops nearly every weekend but calling him a forager is selling what he does quite short. He calls himself a “culinary alchemist” or a “culinary explorer,” and he describes what he does “wildcrafting.”

Other well-known foragers comb the LA terroir. Christopher Nyerges focuses on survival skills. Others are interested in the medicinal value of wild plants. Baudar wants to help devise and foster new wildcrafted culinary cuisine.

Let’s call it forest to table.

Much of Baudar’s experience comes from foraging as a youth, as part of life growing up in Belgium. Baudar turned that knowledge into a profession in the late 1990s, when, as he puts it, the world was about to come to an end (Y2K). His angle then was survival.

He thinks of himself now as primarily a researcher and educator, but there was a time when he worked with award-winning chefs, like Ludo Lefebvre (LudoBites, James-Beard nominated Petit Trois) and Niki Nakayama (n/naka in Culver City—see Netflix Chef’s Table, season 1/episode 4), just to name a couple.

Plenty of famous restaurants employ foragers—Noma is the obvious one that comes to mind, its legendary co-owner and chef, Rene Redzepi, is well known for using native ingredients from the forests of Copenhagen. Brazil’s D.O.M Chef Alex Atala (Chef’s Table season 2/episode 2) is another obvious example.

But clearly California, and more specifically Los Angeles, has its own local terroir, and Baudar is one of its foremost forest whisperers.

Baudar has published two books: “The New Wildcrafted Cuisine,” which has become a well-worn bible for me, and the newly published “The Wildcrafting Brewer,” which includes the whimsical tagline “creating unique drinks and boozy concoctions from nature’s ingredients.” His partner, Mia Wasilevich, is a professional chef and has published “Ugly Little Greens” (“gourmet dishes crafted from foraged ingredients”). Baudar is currently working on a book on lacto-fermentation with wild plants.

Baudar talks in his books about sustainable foraging, by which he means that he typically only takes the plant’s fruit or flowers, or that he replaces plants with their seeds. He also infuses native plants back into the forest where he forages and teaches.

“Through accumulated knowledge, research, observation, and interaction with them, the plants will gladly reveal their deepest secrets and speak your language. For one of my friends, an herbalist, that language is medicinal. As a forager, the plants talk to me about flavors, smell, texture, color, touch, and many other sensory perceptions related to food.”

Fermented Flavor Bombs

Many of Pascal Baudar’s spring workshops this year have been geared around fermentation, in particular, foraging ingredients for sauerkraut, kimchi, or hot sauce, or using some of those same ingredients to make immersions and sodas, which, left to ferment long enough, he says, become a sort of wildcraft wine cooler. Although I can’t really picture the porch-bound Bartles & Jaymes meandering through patches of mugwort or gingerly prying a prickly pear.

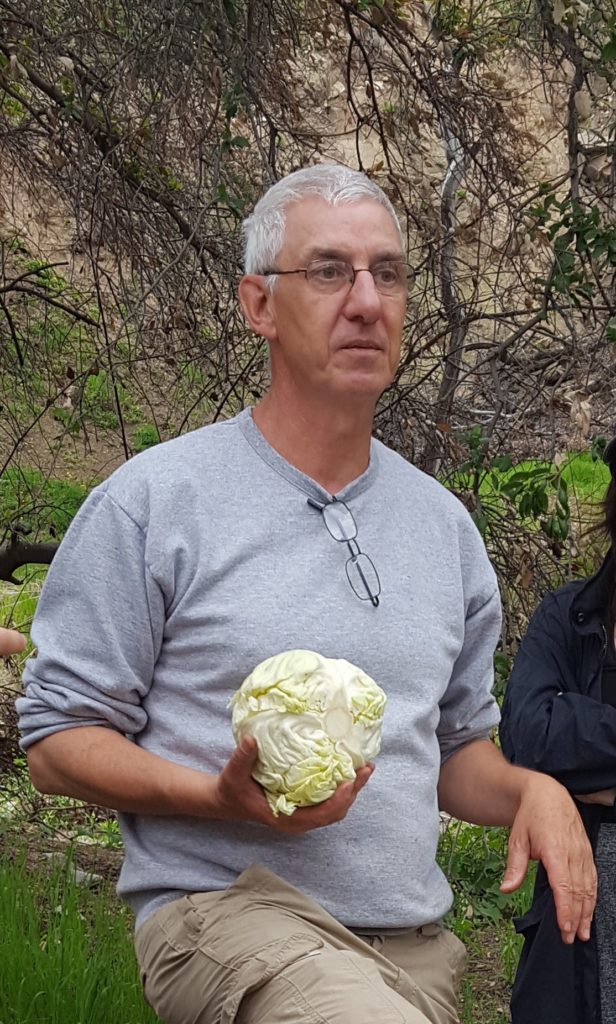

Baudar brought some ingredients to his workshop that we wouldn’t find in the wild—cabbage (“foraged from Ralphs,” he says) for the sauerkraut and kimchi, and jalapenos, habaneros, and bell peppers for the hot sauce, among other items—and he encouraged us to develop our own ideas with our bounty.

Making sauerkraut is really just a matter of mixing salt and cabbage in the right proportion (a couple teaspoons of salt for a pound of cabbage), roughly massaging the cabbage as it begins producing liquid (no gentle Swedish massage here, but more like “50 shades of green,” he quips), and then continuing to soften and extract the water from the vegetable. From there, the rest is open to experimentation with other plants, an intoxicating possibility given that about 80% of what we saw in the forest is edible.

For example, wild mallow, perhaps California’s most invasive wild plant, is rather bland, but it has just a touch of okra flavor and is mucilaginous, so it does well in a hot sauce or paste. Filaree is edible but has no real flavor to it, and yet its purple flower and Edward Scissorhands buds (Baudar’s description, but it’s apt) make it a favorite among chefs. Oxalis (or wood sorrel) has a pungent citrus flavor that is refreshing mixed into a salad. Add the exquisite, miniature lily-pad-like miner’s lettuce, which we found in abundance, and you have a $20 salad, Baudar jokes . . . or come to think of it, maybe he wasn’t joking.

Sweet yellow clover is bitter, but it releases notes of vanilla and cinnamon when you cook it. Chickweed has an herb-like quality. Pineappleweed (a type of chamomile) has a flower that looks and tastes quite a bit like a pineapple. Carpenter ants, which I tried, have a bright lemony spark. Adding them is also good for 10,000 likes on Instagram, Baudar notes.

On the other hand, spurge, which bears a strong resemblance to chickweed, is toxic. Similarly, poison hemlock looks incredibly similar to the edible chervil (tastes of carrot and cilantro). Baudar also shows us the dangerous purple nightshade and jimsonweed, which smells exactly like peanut butter but is psychotropic, and not in a good way.

These would be good for making sauerkraut for someone you don’t like, he jokes. On a slightly more upbeat note, the sap of spurge has been known to cure melanomas, including some of Baudar’s past workshop attendees he says.

Baudar told us he once got a disconcerting phone call from someone looking for information on using harmful plants. It turned out to be someone working on the movie Phantom Thread. (Spoiler alert.) Ultimately this quest led to the noxious mushroom treachery in the film.

Getting Saucy

During his workshop, Baudar shares sauerkraut, kimchi, hot sauce, and paste samples he’d been fermenting or preserving for weeks or months. With some, he had mixed in curry. Others were spicy, including a sublime African spice paste. His “redneck kimchi” was just a variation on the sauerkraut, with heavy helpings of garlic, onion, and pepper.

Sauerkraut, kimchi, and sauces all rely on fermentation, which Bauder explains as feeding the “good bacteria” salt (added) and sugar (plants), with the result being lactic acid. With the hard work occurring through chemistry, our jobs were to ensure a robust environment for fermentation to continue. It’s also important to manage the pressure that fermentation builds in the absence of air. For the first week, we had to push ingredients below the surface level of the liquid (sauerkraut and kimchi) or shake and then leave our jars slightly open throughout the day (hot sauce). Neglecting our fermentations would lead to kimchi and hot sauce bombs.

Infusions, Sodas, and Bug Poop

Infusions are more simple: Take plants, put them in water, add a sugar source (actual sugar, honey, piloncillo, molasses, maple syrup), and place this in a refrigerator for a couple of days. Once again, however, picking the right wild plants is critical.

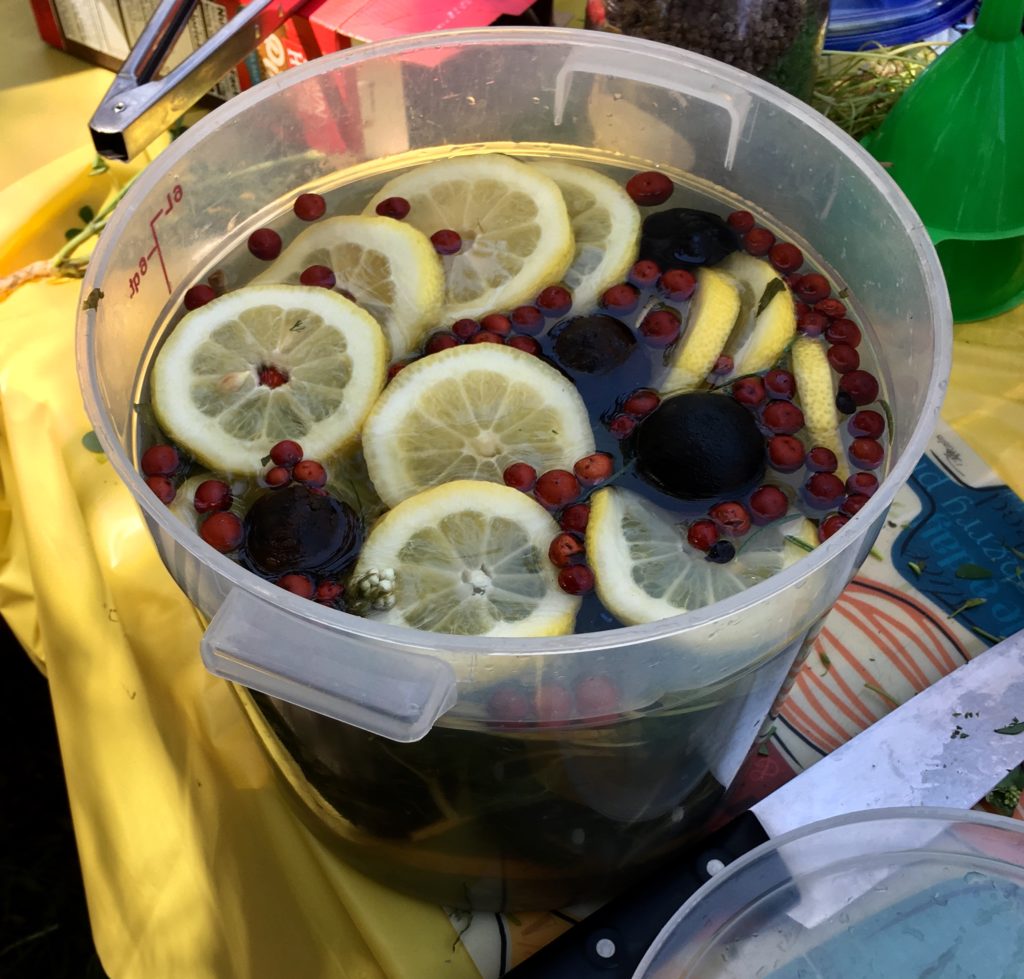

Baudar first demonstrates his “forest floor” infusion, using wild mint as a base, chervil for its herbiness, grass, sweet clover (bitter, but with the right amount, you can extract the vanilla), black sage for vibrant aromatic, California sagebrush (also bitter, but it smells perfumy and divine), and mugwort. Adding lemon (or lime) gives the infusion an acidity that kills bacteria.

You can see in the picture above that Baudar uses Loomi (looks like a black ball), which is a fermented lime, created with a three-minute salt water boil and about two months of sun dehydration. It’s a middle eastern technique, and the lime (black as tar) tastes like candy.

Baudar’s mountain infusion sent my taste buds into virgin territory. He uses pinyon pine (the bark or branch, when opened, smells like honey-glazed spring air), white fir, California juniper berries (crushed), mugwort, and more California sagebrush. He also tossed in some manzanita berries for looks (or Instagram likes, as he is wont to say).

Baudar says that this infusion was a favorite with Ludo Lefebvre’s customers, and was used quite lucratively as a substitute for wine pairings (infusion pairing, in other words).

Making sodas from these infusions is a simple as adding yeast (like a champagne yeast). But why buy what you can make? And so we did. Add a sugar source to water in a 1:4 ratio (if you don’t have enough sugar for the yeast to eat, the soda will be sour) plus yeast. That yeast can come from raw honey or pinyon pine branches or prickly pear or juniper berry or organic blueberry. It can even come from organic grapes. Just toss them into your sugar-water jar with the lid loose (or you’ll be on a watch list for explosive sodas, Baudar warns), shake it throughout the day, and you’ll eventually have a yeast starter.

We tried Baudar’s strained mountain infusion with the yeast starter applied for a couple days. It tastes like a refreshing version Mountain Dew.

Continuing the fermentation for a week will land the composition in the 4-5% alcohol range.

Boozy drinks are a subject for another day, but I’ll leave you with this final flavor bomb: In addition to employing the bitter horehound plant for flavor (pictured above), Pascal often uses lerp sugar for alcohol fermentation. He collects this special ingredient in July from the underside of eucalyptus tree leaves.

It is essentially insect larvae excretion (poop), which forms a protective layer on the leaves. Dehydrated, lerp is 50% sugar, 50% starch, perfect for fermentation. And believe it or not, it’s quite tasty in its dehydrated form, or as Pascal likes to say: “Flavor profile, rice crispy.”

(Headline thoughts rejected for this piece included “LA Forest: Not Just For Fires” and “Wildcrafting: No, It’s Not A Gang Thing, But I Guess It Could Be.”)